Chapter 1: The more you believe in free will, the less free you actually are

Never take anyone's word as absolute fact—especially your own. It's in questioning our most cherished assumptions about free will that we might actually find it.

The Free Will Paradox

"The more you believe in free will, the less free you actually are."

The Awakening

The moment I realized I wasn't in control of my intentions was both terrifying and liberating. It all started when I was just 13 years old. That awkward pre-puberty phase is a strange time for any child. I had two distinct groups of friends then. With my younger friends, I enjoyed the simple pleasures of childhood—playing manhunt and tag, trespassing on private property to build makeshift forts, throwing rotten eggs and toilet paper on Halloween, jumping hills on our BMX bikes and occasionally breaking bones. Life was straightforward, governed by play and adventure.

Then there were my older friends, those who had already crossed the threshold of puberty. I watched them transform before my eyes. Suddenly, girls weren't carriers of some imaginary "cooties" plague but became objects of fascination and desire. This shift confused me, but like any teenager desperate to fit in, I mimicked their behavior. I echoed their words and pretended to share their newfound interest in girls, all while secretly not understanding what the fuss was about. I wanted desperately to mature and experience what they were experiencing.

When my turn finally came, nature's flood of hormones coursed through my veins, and the world shifted on its axis. I'm certain everyone reading this can recall their own version of this transformation: the intense school crushes, the nervously folded "do you like me, check yes or no" notes passed furtively in class, the devastating heartbreak over relationships that barely scratched the surface of real connection. Thinking back to those days and remembering those feelings, it seems like we felt the weight of the world on our shoulders. I'm sure everyone can play their own personal montage in their head—even if you never dated as an adolescent, that montage is probably packed with hidden crushes.

But as my confusion about my older friends' behavior cleared, a more troubling realization took its place. I had tried—genuinely tried—to force myself to be interested in girls before puberty. I had willed it, focused on it, even cried over my failure. Yet all my conscious efforts produced nothing. Then, without my consent or effort, a cocktail of chemicals my body began producing after reaching the long-awaited puberty stage accomplished what all my willpower could not. This revelation was terrifying because it exposed how little control I actually had over my own desires.

If something as fundamental as the drive to procreate could so effortlessly override my conscious will, what else might be lurking beneath the surface of my decisions? If every person is subject to these powerful, unseen forces, can we trust anyone's stated motivations—even our own? How was society not completely corrupted by these hidden drives? (In hindsight, perhaps I was more canny than I realized.) This is where childhood innocence truly ends—when we recognize that everyone, including ourselves, operates with potential hidden agendas. In our modern world, far removed from our cave-dwelling ancestors, we're constantly engaged in a form of deception by omitting these underlying truths from our daily interactions. And yes, when we lie to ourselves about our true motivations, it remains a lie.

Consider what happens when men, in groups with their circle of male friends, have "guy talk"—those unfiltered conversations where men reveal their primal desires with far more detail than most would find comfortable. These same men then have entirely different conversations with their romantic partners, carefully editing their thoughts and desires. The striking part isn't just the difference in content—it's that in each setting, they fully believe what they're saying in the moment, even when expressing completely contradictory viewpoints to different audiences.

We effortlessly shape-shift our "authentic selves" depending on our social context. With friends, family, colleagues, or strangers, we become different versions of ourselves, each version feeling genuine in the moment despite the contradictions between them. This isn't just social adaptation—it's evidence that what we experience as our conscious self is largely performative, a narrative created after our subconscious has already determined our behavior. Our sense of having a single, consistent identity making free choices is perhaps the most pervasive illusion of all.

The Evidence All Around Us

This realization forced me to question everything. What other aspects of myself—my preferences, aspirations, and decisions—were not truly "mine" but simply biological programming disguised as personal choice? Where exactly is the boundary between my individual identity and the survival mechanisms etched into my DNA through countless generations of evolution?

Consider how newborn babies exhibit the suckling reflex—when you stroke their cheek, they instinctively turn toward the touch, mouths opening to nurse. When my first son, Keaton, was born, I was fascinated by this. This behavior isn't taught or chosen; it's hard-wired into their neural circuitry. They couldn't resist this impulse even if they wanted to, nor would they know how. So I wondered: how many of our adult behaviors—behaviors we proudly claim as conscious choices—are actually just sophisticated versions of the same kind of reflexive programming? How many of our decisions are truly conscious?

Consider something as simple as your taste preferences. Do you love cilantro , or does it taste like soap to you? Most people have a strong reaction one way or the other. What's fascinating is that this preference isn't actually a “choice” you made—it's largely determined by your genetic makeup. Scientists have identified specific genetic variants that affect certain taste receptors, making cilantro taste pleasant to some and revolting to others.

What's most revealing is that before learning this fact, people who hated cilantro concocted elaborate justifications for their aversion: "It overpowers the dish," "It reminds me of a bad experience," or "I just never developed a taste for it." They genuinely believed they had reasons for their preference, when in reality, their DNA had already made the decision for them long before they ever tasted the herb.

This is just one small example of how we create post-hoc rationalizations for preferences and behaviors that are actually determined by unconscious factors. We construct logical-sounding explanations for decisions we never consciously made in the first place. If something as simple as a food preference operates this way, imagine how many other "choices" in our lives follow the same pattern.

Think about how political opinions form. Most people believe they've arrived at their political views through careful reasoning and ethical consideration. Yet research shows that identical twins raised apart tend to have remarkably similar political leanings, suggesting a genetic component. Even more telling, brain scans reveal that when presented with information contradicting our political beliefs, the reasoning centers of our brain often shut down while emotional regions light up. We don't reason our way to political positions and then feel good about them—we feel first and construct rational-sounding arguments afterward.

Consider an experiment called "The Ultimatum Game," where one person is given money and must offer a portion to another participant. If the second person rejects the offer, both get nothing. Rational economic theory suggests people should accept any amount (even $1 of $100) since it's better than nothing. Yet most people reject "unfair" offers below 30%, even at personal cost. What's fascinating is how quickly this happens—the brain's emotional response to perceived unfairness fires well before any conscious deliberation. People then create logical-sounding explanations for what was an automatic emotional reaction.

Think about who you've been romantically attracted to throughout your life. Most of us believe we have "a type" based on conscious preferences. Yet studies show that much of attraction is determined by factors outside awareness—major histocompatibility complex genes that govern immune function, hormonal levels at specific life stages, and even unconscious mimicry of early caregivers. People who meet in high-stress environments (like a suspension bridge study) report higher attraction than those in neutral settings, yet attribute it to the person's qualities rather than their physiological state. The unconscious creates the attraction, and consciousness invents a story about personal "choice."

Consider how something as arbitrary as your name influences major life decisions. Studies show people disproportionately choose careers that resemble their names (Dennises become dentists, Lawrences become lawyers) and are more likely to move to cities that share their name (Louisas to Louisiana). We're also more likely to marry people whose names share letters with our own. When asked, people provide thoughtful reasoning for these life choices, completely unaware that their name created a subtle unconscious preference. Yet our names were chosen for us before we had any say in the matter.

In a striking experiment, people were asked to complete a word puzzle containing terms associated with elderly people (like "Florida," "bald," "wrinkle"). Afterward, they walked significantly more slowly down the hallway compared to those who completed neutral puzzles. When asked about their walking pace, none recognized being influenced—they all invented specific personal reasons for their speed. Even more remarkably, people exposed to money-related words became more independent and less helpful to others, all while believing they were making conscious choices about their behavior.

The truth?

Almost NONE of your choices were actually made by you consciously.

How many instinctively called bullshit after reading that? Take a moment to check in with yourself—did reading that last statement trigger feelings of disgust, anger, dismissal, suspicion, or discomfort? The probability that you absorbed that claim without an emotional reaction is very unlikely. This visceral response itself demonstrates my point—we're programmed to reject the notion that we aren't in control, and that very programming is outside our conscious awareness. That automated feeling is what exactly drives this paradoxical loop that makes us believe we are in control.

But what if recognizing this illusion was the first step to actually reclaiming control?

The Neuroscience of Decision-Making

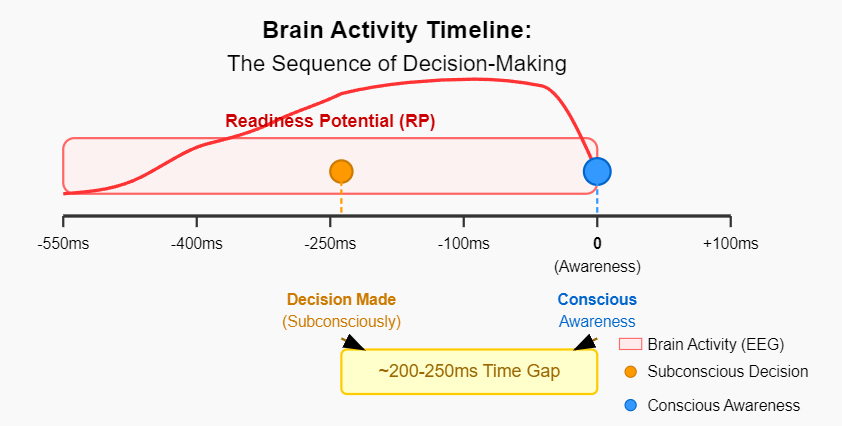

Studies show that we make a decision 550ms before we are even consciously aware of it. Our bodies are so in control of us that they've even installed a tricky feedback loop that makes us double down and back our choices with reasoning, even though we didn't actually make the choice in the first place.

This isn't just theoretical - it's been demonstrated repeatedly in laboratory settings. In the 1980s, neuroscientist Benjamin Libet conducted groundbreaking experiments where participants were asked to perform a simple movement whenever they felt the urge. Using EEG to measure brain activity, Libet discovered something remarkable: the brain's "readiness potential" - a measurable surge in neural activity - began approximately 550 milliseconds before the action, while participants only reported becoming aware of their intention about 200 milliseconds before moving. In other words, the brain had begun preparing for action a full 350 milliseconds before conscious awareness caught up.

More recent studies using fMRI have extended these findings, showing that in some cases, brain activity can predict which choice a person will make up to 7-10 seconds before they're consciously aware of their decision. As neuroscientist John-Dylan Haynes put it, "by the time consciousness kicks in, most of the work has already been done."

Our brains are efficiency machines, constantly seeking to conserve energy. We instinctively follow the path of least resistance. Believing we possess complete free will is far more comfortable than confronting the uncomfortable reality that most of our decisions occur beyond our conscious control. Few would willingly unplug from this comforting illusion—our personal version of the Matrix.

I'm not trying to argue for the simulation theory idea or suggest we live in a computer program. But when we recognize that we're wired to believe we're making conscious choices when we're not, and we're simultaneously programmed to convince ourselves otherwise... what meaningful difference remains between that reality and a simulated one?

Critical Perspectives

However, these scientific findings aren't without controversy. Some researchers question whether the "readiness potential" actually indicates a decision being made or simply reflects the brain's general preparatory state. Others point out that the timing of conscious awareness is notoriously difficult to measure precisely, relying on subjective self-reporting.

Perhaps most significantly, recent research has shown that not all decisions follow this pattern. While spontaneous, arbitrary choices (like deciding when to press a button) show the classic unconscious preparation, deliberate decisions that involve conscious reasoning show a markedly different pattern of brain activity. This suggests that while many of our routine or impulsive actions may be initiated unconsciously, our more thoughtful, value-based decisions might engage different neural processes where consciousness plays a more significant role.

Even Libet himself didn't interpret his findings as eliminating free will entirely. Instead, he proposed that while we might not have "free will" to initiate actions, we might have "free won't" - the ability to veto or approve actions that our unconscious brain has set in motion.

The Paradox Revealed

What these studies reveal is not that consciousness is irrelevant, but that it operates differently than our intuitive sense suggests. Rather than being the originator of our actions, consciousness might be better understood as an oversight mechanism - arriving late to the party, but still having the ability to shape the outcome.

This aligns with our earlier observations about social and biological influences on behavior. Just as puberty transformed my desires without my conscious input, neuroscience confirms that many of our seemingly "free" choices begin as unconscious neural events before rising to awareness. Our sense of being the authors of our actions may be partially constructed after the fact, as the brain creates a coherent narrative of intention and control.

"The paradox deepens: the more science reveals about how decisions actually form in our brains, the more we see that conscious will often arrives too late to be the true cause. Yet it's precisely this illusion of control that allows us to function effectively in the world."

Despite all the research and competing theories, no one actually knows precisely how consciousness works or exactly where the boundary lies between nature's programming and genuine autonomy. But here's what makes this paradox so powerful: the answer to that question isn't what matters most. Asking the right questions is more powerful than finding the right answer.

What matters is recognizing the patterns in your own life—moments where you believed you were in complete control, only to later realize unseen forces were guiding your hand. It's about developing the awareness to question not just others' apparent certainties, but your own as well.

The first step toward genuine freedom isn't clinging to the illusion of total control—it's acknowledging how little control we actually have. Only by recognizing the invisible strings can we begin to see which ones might be cut, and which ones we might learn to pull ourselves.

As we explore the other paradoxes in this book, remember this fundamental truth: everyone, including me, has only a piece of the puzzle. The only way to secure any real measure of control is to formulate your own mental framework based on careful observation and critical thinking. Never take anyone's word as absolute fact—especially your own. It's in questioning our most cherished assumptions about free will that we might actually find it.

And perhaps the most troubling part of this illusion of control? Those who have reflected the least on the unconscious forces driving their behavior tend to be the most confident that their choices are entirely their own—setting the stage for an even deeper paradox about the nature of thought itself…

The Paradox Framework Applied

Revelation Layer

The free will paradox creates profound cognitive dissonance by challenging our most fundamental belief about ourselves: that we consciously control our choices. Discovering that our brains make decisions before we're consciously aware of them disrupts our entire understanding of agency and identity. This disruption creates a rare opportunity to see the automatic processes that typically operate below conscious awareness.

Recognition Layer

This paradox helps you recognize specific patterns in your experience:

Moments when you act "on impulse" and rationalize your behavior afterward

Recurring decisions that follow predictable patterns despite intentions to choose differently

How your choices seem to align suspiciously well with biological drives and social conditioning

The illusion of deliberation when you've already unconsciously committed to a path

Reflection Layer

These patterns likely developed from:

Evolutionary advantages of believing we control our actions

Cultural narratives that emphasize individual choice and responsibility

The brain's need to create coherent narratives about our behavior

The psychological protection that comes from believing we determine our fate

Reprogramming Layer

With this awareness, new possibilities emerge:

Observing your decision-making processes with greater curiosity and less judgment

Recognizing the gap between impulse and action where choice becomes possible

Creating systems that shape your unconscious tendencies rather than fighting them

Developing compassion for yourself and others when recognizing the power of unconscious programming

Finding authentic freedom not in denying programming but in becoming aware of it

For the next 24 hours, pay close attention to "spontaneous" decisions—moments when you suddenly reach for your phone, decide to get a snack, or shift position in your chair. Try to catch the exact moment you become aware of the intention to act.

You'll likely notice that by the time you're conscious of the urge, your body is already in motion.

Now, occasionally, try to "veto" these impulses once you become aware of them. Can you stop the action that's already begun?

Reflection Questions:

- How long was the gap between unconscious initiation and conscious awareness?

- Which impulses were easier to veto, and which seemed impossible to override?

- How did this exercise change your understanding of your own decision-making?

- When you successfully vetoed an impulse, what did that experience feel like?

This exercise helps you experience firsthand the gap between unconscious initiation and conscious awareness, while also exploring your capacity for conscious intervention—what neuroscientist Benjamin Libet called "free won't" rather than "free will."