Chapter 13: The Paradox of Reality - From 3D to 2D to One Profound Truth

How perception creates different versions of reality for each person, and why consensus reality is both necessary and limiting. Explore the boundaries between objective truth, shared illusions, and personal experience—and why this matters in an age of information abundance.

The Day My Reality Shattered

I always thought the programming I'd been exploring throughout this book affected our thoughts and decisions—but I never imagined it extended to something as fundamental as vision itself. Yet my experience with cataracts revealed just how deeply our brains construct even our most basic perceptions.

The monthly 2.5-hour drive to visit my parents in Pennsylvania was a routine I'd grown comfortable with. Years ago, my parents had adopted two children—a brother and sister with life-threatening issues at birth—to keep them together and provide the love they needed. With an empty nest, it worked perfectly. Christian and Savana became family while also being aunt and uncle to my children, despite being similar in age. Despite the confusing technicality, they all enjoyed playing together and getting into trouble.

During one of these drives, I noticed something disturbing. Even without high beams, oncoming headlights temporarily blinded me. For 1-3 seconds while passing another vehicle, I was effectively blind at 60 mph, while the other car maintained similar speed. Each time, panic seized me—knowing I was responsible for four innocent, excited children in my care. Eventually, I silenced their chatter and asked:

"Guys, is it me, or are other people's headlights brighter than ever?"

Puzzled by the question's context, they responded with uncertainty: "Um, yeah, I think so, maybe." I couldn't understand why this had never been an issue before. Rather than dwell on it, I made a simple decision: no more night driving with my precious cargo.

Orange Glasses and Social Experiments

One day while running errands, a product caught my eye—deep orange-tinted glasses marketed to elderly people, showing them panicking while driving with exaggerated headlights coming toward them. I realized I wasn't alone. "I'm just getting old, I guess," I thought. Problem solved.

Wearing these stereotypical "old person" glasses changed my social interactions. Friends jokingly poked fun, with one particular friend making it his mission to comment every chance he got. Rather than be annoyed by the implication that my vision issues were legitimate, I decided to double down and wear them all the time.

I made a silent rule: I wouldn't ask anyone to try them on, but I'd take a picture of anyone who asked to wear them while friends were being silly. This impromptu social experiment resulted in a heartwarming album filled with strangers, friends, and family all smiling, laughing, and posing while wearing these $5 AutoZone glasses.

The orange glasses became more than a visual aid—they became a laboratory for understanding how perception shapes social reality. Just as our mental programming shapes how we see the world, those glasses physically altered both how I saw others and how they saw me. But most fascinating was how quickly a new 'normal' established itself. Within days, orange became my baseline—much like we normalize the mental filters that shape our perception of everything from politics to relationships.

This album became one of my prized possessions and taught me about the power of breaking social scripts. Seeing through an orange lens changed how people saw me, but I also adapted to seeing everything in orange. I noticed that removing the glasses created a different visual experience—my eyes had adjusted to processing the world through an orange filter, changing how they rendered colors when the glasses came off.

When Vision Betrays You

It was interesting, but I began wondering what was really happening. My research pointed to something I didn't want to accept: cataracts. The first symptom matched exactly the car headlight issue that had initially scared me. But how? I was only in my mid-30s, and the likelihood seemed very low. Then one day, reality shifted dramatically.

Driving back from the warehouse where I managed my 55 3D printer farm, I turned onto the highway ramp, still worrying about the possibility of cataracts. How could the lenses in my eyes be clouding up and developing a dirty orange-brown tint? Suddenly, something felt off. The sky looked strange. I removed my orange glasses, and my heart sank. During full daylight, everything around me was orange.

HOW? WHAT? I'M NOT EVEN WEARING THE GLASSES!

The sudden change terrified me. Was this fixable? Would everything look like this forever? Was I doomed to see only in dull, dingy orange? I pulled into the nearest gas station to get my bearings.

As I walked toward the door, feeling this was my new reality—what I can only describe as what hell might look aesthetically—I overheard another customer on the phone: "Yeah, it's crazy... everything is orange, I know."

Wait... What? Others see it too? My confusion deepened. What was happening? Was this some kind of Truman Show experiment? No. It turned out to be a rare weather phenomenon affecting the east coast that day. The scene from Men in Black immediately came to mind, as I tried to pinpoint when the "flash" might have occurred.

My eyes were fine—or so I thought.

The Hallucinations Begin

Over the next month, something disturbing began happening during my daily two-hour drives to and from the print farm. Things I knew I saw would simply disappear. Objects transformed as I approached them. A person walking a German Shepherd would turn into a rock and stick.

"I'm working too hard," I reasoned. "This must be why I'm going crazy." I tried to laugh it off with self-deprecating humor, but inside I was terrified. Life had to continue, even through mirages and hallucinations. I knew I wasn't sleep-deprived, taking medications, using drugs, or hungover. I was fine—until I realized I wasn't, at almost the cost of my life.

Driving 60 mph on Route 280 during a beautiful spring day, everything seemed normal. The trees were blossoming, it was finally warm enough to roll down the windows and turn up the music.

Then I saw her—a little girl, about five years old, wearing a black and white plaid dress, appearing directly in front of my car about 3 seconds away.

I slammed on the brakes and yanked the steering wheel right, narrowly missing the car in the adjacent lane. Panicked about the child's safety, I jumped out without concern for my own danger.

My heart sank, now filled with confusion and shame. There was nothing there—just road markings that, from a specific angle, had created the illusion of a small child. My brain had lied to me. I ran back to my car, embarrassed by the danger I'd caused.

My brain had seamlessly integrated input from my clouding eyes, constructing a perception of reality where my vision seemed perfectly normal. I had absolute confidence in my perception, never questioning whether what I "saw" reflected objective reality. My brain was simply doing what it always does. It takes all the data it has and fills in the blanks.

In that split second of terror, as I swerved to avoid hitting a child who wasn't there, everything I thought I knew about perception shattered. This wasn't just a minor visual glitch—it was proof that my brain had been quietly rewriting my reality without my consent or awareness. If my mind could fabricate a child in the middle of a highway, what else in my life was it silently constructing for me?

This wasn't a minor oversight—it was a complete fabrication created by my brain. Most disturbing of all, I had been entirely unaware of the deception. That day planted a question that would haunt me: If my brain could construct such a convincing illusion about something as basic as vision, what else might it be fabricating without my awareness?

The Perception Construction Site

Just as we saw with free will in Chapter 1, where our brain makes decisions before we're consciously aware of them, my visual system was constructing a reality I accepted as objective truth. The comfort trap from Chapter 3 played out as well—my brain preferred the comfort of its familiar construction over the discomfort of acknowledging my failing vision.

This experience was my introduction to what neuroscientists now confirm: perception is not passive reception but active construction. Your brain doesn't simply record reality like a camera—it actively builds your experience from limited, often ambiguous information. Consider what happens when you "see" anything. Light enters your eyes, activating photoreceptors in your retina that convert light energy into electrochemical signals. These signals travel through your optic nerve to your brain, which then constructs a coherent experience from this raw data.

But here's where it gets interesting: your visual cortex is doing most of the heavy lifting. Up to 90% of what you "see" is constructed by your brain based on context, expectations, and prior knowledge—not from direct input from your eyes. Vision is just the beginning. Every form of perception involves similar construction. Take hearing. When someone speaks to you, the sound waves that reach your ears are often incomplete—drowned out by background noise. Yet you generally hear complete words and sentences because your brain fills in the blanks based on context and expectation.

The McGurk effect demonstrates this brilliantly. If you watch a video of someone saying "ba" but the audio plays "fa," your brain will often perceive "va"—a sound that exists in neither the actual audio nor the visual cue. Your perception has created an entirely new reality. Touch, smell, taste—all our senses operate this way. We don't experience reality directly; we experience our brain's best guess about reality based on limited input and elaborate construction.

This construction isn't a defect—it's a feature. Your brain has evolved to create useful, simplified models of an infinitely complex environment. These shortcuts allow you to navigate the world efficiently without getting overwhelmed by sensory information. But there's a cost: what you experience as "obvious reality" is actually a heavily edited and interpreted version of what's actually out there.

The Reality Filters

Beyond basic sensory construction, we all perceive through multiple layers of filters that further shape our experience of reality:

The Biological Filter

Your species-specific biology creates the first filter. Humans can only perceive a tiny fraction of the electromagnetic spectrum as visible light. We miss ultraviolet light that bees can see, infrared radiation that snakes detect, and countless other aspects of reality our sensory equipment simply isn't designed to capture.

Even among humans, biological differences create different perceptions. About 8% of men have some form of color blindness. Are they seeing reality "wrong," or are the rest of us? The question becomes absurd when you realize there's no privileged perspective.

The fastest we can consciously register distinct images is about 13 milliseconds. Events happening faster than this timeframe are invisible to us, yet they're still part of objective reality. Meanwhile, our hearing range (roughly 20Hz to 20,000Hz) means we're deaf to the ultrasonic world of bat echolocation or the infrasonic rumbles elephants use to communicate over miles.

The Psychological Filter

Beyond biology, your individual psychology profoundly shapes your reality. In a famous 1954 experiment, Princeton and Dartmouth students watched the same football game between their schools. When later questioned about the game, they literally "saw" different fouls and infractions depending on which team they supported. Their allegiance literally changed what they perceived.

Our expectations, desires, fears, and beliefs act as powerful reality filters. Confirmation bias causes us to notice evidence that supports our existing beliefs while remaining blind to contradictory information. Studies show that identical resumes are perceived differently based solely on the gender or ethnicity of the name at the top.

Even more fascinating is how we filter our internal realities. Memory, far from being a faithful recording, is constantly reconstructed. Each time you recall a memory, you're not accessing the original but creating a new version—often subtly altered to fit your current narrative. Your memory of your past is itself a construction, not a retrieval.

The Cultural Filter

Beyond individual psychology lies the collective filter of culture. Language itself shapes perception in ways we're only beginning to understand. Speakers of languages that use different words for light blue and dark blue can distinguish between these shades more quickly than English speakers who categorize both as "blue."

The Himba tribe in Namibia has no distinct word for blue but has multiple words for different shades of green. When shown a circle of green squares with one blue square, many Western observers immediately spot the blue square. Himba participants often struggle with this task—not because of deficient vision, but because their language doesn't emphasize this particular color distinction.

Cultural narratives shape our expectations, which in turn shape our perceptions. A person raised in a culture that believes in communication with ancestors might interpret certain mental experiences as visitations from the dead, while someone from a secular scientific background might interpret identical experiences as hallucinations or dreams.

The Technological Filter

Perhaps most relevant to our current moment is how technology increasingly mediates our experience of reality. Social media algorithms determine what information reaches us, creating individual reality bubbles where different people experience entirely different "truths" based on their engagement history.

Virtual and augmented reality technologies are deliberately designed to manipulate perception. But even "neutral" technologies like smartphones change how we experience reality by altering where we direct our attention. Studies show that simply having a smartphone visible (even face down) reduces cognitive capacity and attention to the present moment.

When these filters operate in combination—as they always do—the distance between "objective reality" and your subjective experience of it becomes vast. And here's where the paradox emerges: the more you understand about perception, the more you realize how constructed your experience truly is.

The Scientific Evidence

The constructed nature of perception isn't philosophical speculation—it's established science. Here are just a few examples of research demonstrating how profoundly our perception creates rather than reflects reality:

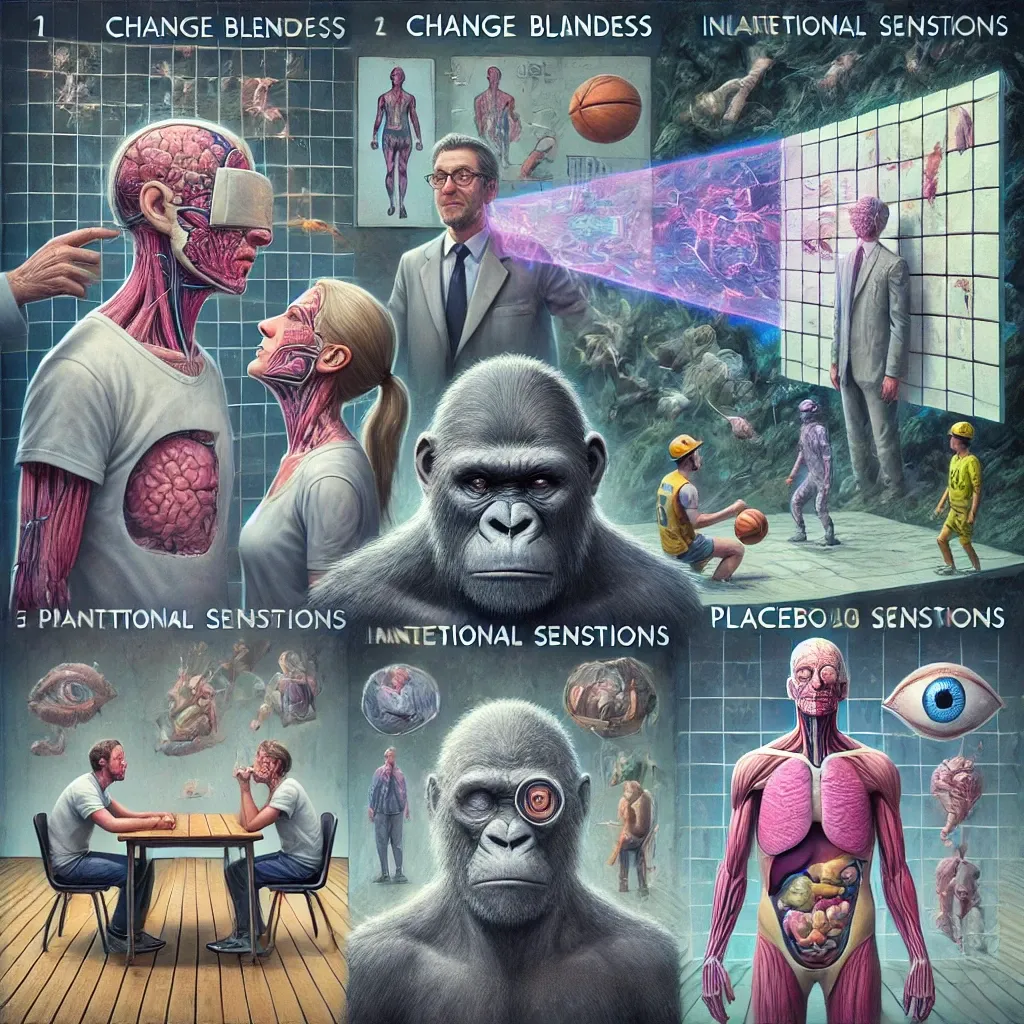

Change Blindness

In change blindness experiments, researchers show participants images that change in obvious ways, yet most people fail to notice these changes if they're briefly interrupted or distracted. In one famous experiment, a researcher asking directions was secretly switched with an entirely different person during a momentary distraction, and over 50% of participants failed to notice they were now speaking to someone completely different.

This demonstrates that we don't actually see everything in our visual field—we construct a simplified model and only update it when our attention is specifically directed to changes.

Inattentional Blindness

The famous "invisible gorilla" experiment shows this even more dramatically. When asked to count passes in a basketball video, about 50% of viewers fail to notice a person in a gorilla suit walking through the scene, thumping their chest. The gorilla is fully visible for nine seconds, yet half the viewers swear it wasn't there.

This isn't a minor perceptual glitch. It reveals that unless we're specifically attending to something, it simply doesn't become part of our conscious reality—even when it's right in front of us.

Phantom Limb Sensations

Perhaps the most striking evidence comes from phantom limb experiences, where amputees continue to feel sensations (often painful ones) from limbs that no longer exist. This phenomenon reveals how much of our bodily experience is constructed by our brain rather than directly received from sense organs.

V.S. Ramachandran's groundbreaking work with mirror boxes—where amputees can see a reflection of their existing limb in place of the missing one—shows how providing visual input that contradicts the brain's model can actually reduce phantom pain. The brain updates its construction based on new visual evidence, even when that evidence is an illusion.

Placebo and Nocebo Effects

The placebo effect—where inactive treatments produce real physiological benefits—demonstrates how belief directly shapes biological reality. Even more telling is the nocebo effect, where negative expectations produce real harmful effects.

In one striking study, patients were given an inert cream but told it would increase pain sensitivity. When subjected to a mild pain stimulus, they reported significantly more pain than control groups. Their expectations literally created their pain experience.

Breaking Down the Illusion

So where does this leave us? If everything we experience is a construction, is there any way to access "true" reality?

The paradox deepens here: the tools we use to investigate reality are themselves products of our perceptual systems. Science, our best method for overcoming individual biases, still depends on human observation and interpretation. Even our most sophisticated measuring instruments must ultimately be read and understood by human minds.

This doesn't mean we should abandon the pursuit of understanding reality. Rather, it suggests we need to adopt a more sophisticated approach that acknowledges the constructive nature of perception while still seeking to refine our models.

Here's how we might navigate this paradox:

Radical Humility

The first step is embracing radical epistemic humility—acknowledging that our confidence in our perceptions is often wildly overblown. The person most convinced they're seeing reality clearly is often the most deeply captured by unexamined filters.

This humility isn't about doubting everything—it's about holding our perceptions lightly, remaining open to evidence that our constructions might be incomplete or misleading.

Multiple Perspectives

Since each person's reality construction is filtered differently, engaging with diverse perspectives becomes essential. The closest we can come to objectivity is through the integration of many different subjectivities.

This approach doesn't treat all perspectives as equally valid in all contexts. Rather, it recognizes that different filters may reveal different aspects of reality, and that a more complete picture emerges through integration.

Metacognitive Awareness

Developing awareness of your own reality construction process—metacognition—is perhaps the most powerful tool for penetrating the illusion. By observing how your mind constructs experience in real-time, you can begin to distinguish between the raw data and your interpretations of it.

Meditation practices specifically designed to increase this awareness have been shown to improve perceptual accuracy and reduce cognitive biases. The mind observing itself becomes less captive to its own constructions.

Technological Augmentation

Ironically, while technology can further separate us from direct experience, it can also help us overcome perceptual limitations. Instruments that detect radiation beyond our sensory range, algorithms that identify patterns too complex for human recognition, and simulations that challenge our intuitions can all expand our access to aspects of reality beyond our native filters.

The key is using technology as a supplement to, not a replacement for, direct perception—and remaining aware of how technological filters themselves shape what we experience.

The Liberation of Uncertainty

There's something deeply unsettling about recognizing how constructed our reality is. The solid ground of certainty dissolves beneath our feet. If we can't fully trust our perceptions, what can we trust?

Yet this uncertainty can be profoundly liberating. Once you recognize that your experience is constructed, you gain new freedom to examine and potentially reconstruct it.

Consider how this applies to something as foundational as the self. Most people experience themselves as solid, continuous entities. But neuroscience increasingly suggests that the self is another construction—a useful fiction created by the brain to organize experience.

When you observe your own consciousness carefully (as long-term meditators do), you begin to notice how thoughts, emotions, and sensations arise and pass without a solid "self" anywhere to be found. The very sense of being a continuous entity is itself a perceptual construction.

This insight can transform how you relate to difficult experiences. If your self is a construction, then painful emotions like shame, inadequacy, or unworthiness are not reflecting some fundamental truth about you—they're temporary constructions that can be observed and potentially reconstructed.

The paradox extends to social reality as well. Institutions, laws, nations, money—these exist only because we collectively agree they do. They're social constructions that feel solid only because we rarely examine their constructed nature.

Once you recognize this, social change becomes more conceivable. The structures that appear most permanent and inevitable are often the most dependent on collective agreement—and thus potentially the most vulnerable to reconstruction.

Reality as a Creative Process

Perhaps the most profound implication of the reality paradox is that perception is not just constructive but creative. You are, in a very real sense, participating in the creation of your reality through the act of perceiving it.

This doesn't mean reality is completely subjective or that you can manifest material changes through thought alone—the physical world operates according to patterns that exist independently of our perception. But your experience of that world—which is the only reality you'll ever know directly—is a creative collaboration between external patterns and your perceptual processes.

The quantum physicist John Wheeler captured this idea with his concept of the "participatory universe," where observers are not passive recipients but active participants in creating reality. While we should be careful not to overstate quantum effects at the macro level, the principle remains powerful: the line between perceiving reality and creating it is blurrier than we once thought.

This creative participation becomes even clearer in the social world, where our collective beliefs literally shape institutional realities. Money has value because we collectively agree it does. Laws have power because we collectively submit to them. These aren't discoveries about pre-existing reality—they're creative acts of collective construction.

The Way Forward

Living in awareness of the reality paradox doesn't mean abandoning the pursuit of truth or falling into nihilistic relativism. Instead, it means engaging with reality more skillfully, with greater awareness of the constructive processes that shape your experience.

Here are some practical approaches to living with this awareness:

Perception Checking

Make a habit of checking your perceptions against other sources. When you have a strong reaction to something, ask: "Is this how others would perceive this situation? What might I be missing or adding?"

Assumption Hunting

Regularly examine the assumptions underlying your perceptions. Ask: "What am I taking for granted here? What would change if those assumptions weren't true?"

Filter Switching

Deliberately try on different perceptual filters. If you're politically progressive, read thoughtful conservative analyses of current events. If you're science-oriented, explore artistic or spiritual perspectives on the same phenomena.

Sense Refinement

Train your perceptual systems to detect more nuance and detail. Wine tasting, music appreciation, meditation, drawing classes—all these activities can refine your sensory capabilities and reveal how much richer reality is than your default construction of it.

Reality Testing

When facing important decisions, explicitly test your perceptions against available evidence. Ask: "What observable data supports or contradicts my understanding? What would disconfirm my current model?"

These practices won't give you access to some mythical "objective reality" beyond all filters. But they can help you construct more useful, more accurate, more comprehensive models of what's actually happening—both around and within you.

Seeing With New Eyes

My experience with cataracts taught me something crucial about freedom: true liberty doesn't come from escaping our perceptual constraints—that's impossible. It comes from becoming aware of them. Just as recognizing our lack of free will is paradoxically the first step toward genuine choice, acknowledging the constructed nature of perception is the first step toward seeing reality more clearly. We don't become free by escaping our programming—we become free by understanding it.

Eventually, I underwent cataract surgery in one eye. What followed was nothing short of revelatory. The morning after the procedure, I stepped outside and nearly gasped. The world exploded with color. Street signs I hadn't realized were blurry now appeared in sharp focus. Colors I'd been seeing as muted and dingy revealed themselves as vibrant and alive. Most striking was the realization that I hadn't known what I was missing. My brain had so thoroughly normalized my diminished vision that I hadn't fully comprehended how much of reality was being filtered out.

"So this is what everyone else sees," I thought, both amazed and slightly unsettled by how confidently I'd navigated a world that, in retrospect, I'd only been partially perceiving. The surgery came with its own paradoxical limitations. My new artificial lens had a fixed focal point, requiring reading glasses to see my phone while making the rest of the world slightly blurry. I had traded one perceptual limitation for another, yet this new constraint felt like an acceptable bargain for the restored clarity.

The Perfect Irony: From 3D to 2D

Weeks after my cataract surgery, I sat in my workspace, eager to test a cutting-edge AR headset—a moment I believed would mark the pinnacle of immersive 3D experiences and the future of human perception. For years, my passion for 3D printing had defined my world; depth, texture, and intricate layers were not just visual elements—they were the very essence of my creativity and identity.

So when I loaded the 3D video, expecting the familiar thrill of stereoscopic wonder… nothing happened. The footage was flat, devoid of the depth I’d always taken for granted. I frowned, double-checked the settings, restarted the headset—still nothing. My first thought was, “What could I possibly be doing wrong?” Then, it hit me like a gut punch. It wasn’t the headset—it was me. I was no longer capable of seeing in stereoscopic 3D. I sat there, stunned. At first, a wave of grief washed over me—not for the loss of physical eyesight, but for what it signified. How could 3DMikeP, the man who built his identity on creating vibrant, dimensional realities, now see the world in flat 2D? It felt like a cruel joke, a cosmic irony so biting that I couldn’t help but let out a bitter laugh.

Depth perception had always been second nature—a seamless illusion crafted by the brain, stitching together two separate images into one unified experience. And now, that illusion had crumbled. The realization was not just intellectual; it resonated deeply within me. I felt as though I’d lost something fundamental. Yet, in the midst of that shock, curiosity began to seep in. If I had never known I lost my depth perception, how many other hidden dimensions had I been missing? How many assumptions about the world had I carried without question?

As I gazed down at the AR glasses in my hands—once a symbol of my mastery over 3D perception and an emblem of my red and blue 3D glasses branding that defined 3DMikeP—I realized the irony wasn’t a loss at all. It was a revelation. I had spent my life obsessing over layers and complexity, only to be taught a humbling lesson in the fragility of perception.

From Losing Something to Gaining Something Greater

My mind flashed back to my last company, Assembyl 3D, where we occasionally made prosthetics for children in need—free of charge.

I always knew that these kids, in reality, were fully capable without a prosthetic arm. They had already adapted to doing everything other kids could do. But society saw them as incomplete. So instead of just giving them something that “filled a void,” we made something empowering. A custom Nerf gun arm? A magnetized hand with interchangeable tools? We turned what others saw as a limitation into an advantage. And here I was—facing my own version of that same question.

I wasn’t just someone who lost depth perception. I was someone who now understood depth in a way few people ever could. That realization unlocked something in me. What if I could enhance my vision in a way others couldn’t? What if AI-powered vision could augment my reality, compensating for what I lost?

What if this wasn’t a limitation—but an opportunity? My first thought: How can I add an AI vision camera to these AR sunglasses? Understanding these niche vision issues firsthand gave me an unparalleled ability to experience, identify, and solve them. Instead of treating this as a loss, I started thinking of it as an edge—a chance to innovate for an entire demographic of people living with vision issues. And as I sat there, still staring at my AR headset, the irony clicked in full. I had physically lost a dimension, but mentally gained one. Instead of hiding from it, I embraced it. Introducing this embodiment of all these learned lessons....

PRESENTING: 2DMikeP

The very tools that once celebrated the dynamic interplay of red and blue 3D vision now underscore the creative transformation of seeing the world in a new light. Just like those ancient cardboard 3D Movie theater glasses, flatness wasn’t a limitation—it was an invitation to explore and reconstruct reality with fresh eyes. Perhaps losing one dimension helped me see reality more clearly than ever before.

The Ultimate Paradox

The reality paradox contains within it a final twist. If all perception is construction, then even your understanding of perception as construction is itself a construction. This creates a strange loop—a self-referential paradox where the very tools you use to understand reality are products of the reality-construction process you're trying to understand.

Yet somehow, this recursive loop doesn't collapse into meaninglessness. Instead, it opens into something more profound: the recognition that you are both the observer and the creator of your experience, both constrained by reality's patterns and participating in their expression.

This paradox doesn't resolve neatly. But living within its tension—holding both the humility of knowing your perceptions are constructed and the responsibility of knowing you participate in that construction—may be the closest we can come to genuine wisdom about the nature of reality. And perhaps the most liberating insight of all is this: the recognition that reality is partly constructed doesn't make it less real—it makes you more powerful in how you engage with it.

Try This:

The Reality Filter Experiment

For one week, deliberately adopt a different reality filter each day:

Day 1: The Detail Filter

- Notice five details in your environment that you normally overlook. How does bringing these details into your awareness change your experience of reality?

Day 2: The Connection Filter

- Look for connections between seemingly unrelated events or objects. How does perceiving these connections change your understanding of causality?

Day 3: The Beauty Filter

- Seek beauty in places you normally find mundane or uninteresting. How does this intention shape what you actually perceive?

Day 4: The Confusion Filter

- Approach familiar situations as if you don't understand them. What new questions arise when you suspend your usual interpretations?

Day 5: The Character Filter

- Imagine yourself as a different personality type (more extroverted if you're introverted, more analytical if you're intuitive, etc.). How does this shift your perceptions and reactions?

Day 6: The Possibility Filter

- Look for potential and opportunity in situations you normally find limited or constrained. How does this change what actions seem available to you?

Day 7: The Integration Filter

- Combine insights from the previous days. How has your understanding of reality construction evolved? What remains solid, what feels more fluid?

Throughout this experiment, keep notes on:

- How intentionally shifting filters changes your direct experience

- Which filters feel most challenging or uncomfortable to adopt

- What aspects of reality seem most malleable or constructed vs. most fixed or independent of your perception

The goal isn't to determine which filter is "correct," but to experience firsthand how your intentional approach to perception shapes what you actually perceive—revealing both the constructed nature of experience and your creative participation in it.