Chapter 12: The Mirror Effect – Why Parenting is the Ultimate Self-Discovery Tool

Children reflect and magnify the unconscious patterns in their parents. Learn why your child's most frustrating behaviors are often showing you your own unresolved issues, and how this awareness creates opportunities for mutual growth.

The Memory That Wasn't There

One summer at 16 years old, I stayed at my Aunt Pam and Uncle Epis's house in Pennsylvania. I treasured these visits because they were the first times I was treated like an adult. During one casual conversation, my uncle's friend was expressing empathy for Eminem's difficult childhood when my uncle interrupted with something that would echo in my mind for years:

"So what? Everyone has it hard. Just look at Michael. He's had it hard too, what's the difference?"

His matter-of-fact tone stunned me. I hadn't had it hard at all—or so I thought. What was he talking about? Either this man I deeply respected was completely clueless, or I was missing something fundamental about my own life.

It was me who was missing something.

It happened in the most ordinary place a 7-Eleven, fluorescent-lit and smelling of cheap coffee and stale hot dogs. I was 29 years old and just grabbing something quick when an elderly woman approached me, her face lighting up with recognition.

"Oh my goodness," she said warmly, "look at you! I haven't seen you in years."

I glanced at her, trying to place her face. Nothing. She was a sweet elderly Black woman, the kind of grandma who radiated warmth—the kind who makes you feel safe just by standing near her. Something about her even reminded me of my Norwegian grandmother, who had all those same gentle, caring qualities. But despite the familiarity in her energy, I had no clue who she was.

She saw the confusion on my face and chuckled, shaking her head with the kind of patience only grandmothers and teachers seem to master.

"You don't remember me, do you?" she asked, still smiling.

I hesitated, embarrassed. "I'm so sorry," I admitted. "I don't."

She reached out and patted my arm, her voice full of understanding. "That's okay, sweetheart. I was your third-grade teacher."

My third-grade teacher.

The words hit like a misplaced puzzle piece that didn't fit anywhere in my mind. I searched for something—anything—that might trigger a memory. A classroom. A desk. The sound of her voice reading a book. The feeling of sitting in her class, listening to a lesson.

Nothing. Just emptiness.

I must have looked completely lost because her expression softened. "That's okay," she said gently, her voice dipping into something quieter, more knowing. "Sometimes when we'd rather not remember something, our bodies step in to help us not stress."

I nodded dumbly, still scrambling to make sense of it. A whole year of my life—gone. No fragments, no vague impressions, just a clean, surgical absence where third grade was supposed to be.

At that moment, standing in the checkout line of a gas station convenience store, I felt something I couldn't quite name. At the time, I would have called it mortification—the sheer discomfort of realizing someone had once known me, taught me, cared about me, while I had no recollection of them at all. But thinking back now, maybe that wasn't quite it. Maybe the feeling was something deeper, something I hadn't been able to process at the time.

Because the real question wasn't just *Why don't I remember?*—it was *What happened in third grade that my mind decided I shouldn't?*

Somewhere in my past, something had been too much. Too painful. Too destabilizing. So my brain did what brains sometimes do—it erased the year. It built a blank space where the hard parts should have been, a silent act of self-preservation.

And here was this woman, unknowingly holding a missing piece of my past, smiling up at me like I was the same kid she had known all those years ago.

I smiled back, thanked her, and walked out of that 7-Eleven with my bag of snacks and a hole in my memory I hadn't realized existed until that moment.

I still don't know what was erased. And maybe I never will. But that moment—that absence—became one of the most important things I've ever remembered.

When Children Become Our Teachers

That 7-Eleven encounter cracked open a truth I wouldn't fully understand until years later, watching my sons grow: our children aren't just carriers of our genes—they're living mirrors of our unfinished selves. They inherit not just our DNA but the invisible architecture of our wounds, and reflect them back with a clarity that strips away our defenses.

The Physical Mirror

It began with Westen's clubfoot—the same condition I was born with. Those weekly trips to Manhattan weren't just doctor visits; they were portals through time. As doctors molded his tiny support brace, I could feel the phantom pressure of those same "bars" my parents had described me wearing. The stories I'd heard my whole life suddenly materialized in three dimensions. I wasn't just a father taking his son to treatment; I was witnessing my own history replayed, standing invisibly beside my mother as she once sat in that same sterile room, holding the baby version of me.

But the physical mirror was merely prelude.

The Emotional Echo

When Westen's personality emerged, something inexplicable happened. A heaviness would settle in my chest whenever I was alone with him—a discomfort so profound and disturbing I couldn't name it. A terrible question haunted me: What kind of monster doesn't love all his children equally?

I buried this feeling, ashamed to even acknowledge its existence. It hid in plain sight deep down while I constantly pushed it down further. Then came the revelation that broke me open: Westen wasn't triggering my discomfort because I loved him less—he was triggering it because he reflected me at my most vulnerable. Not the adult Mike, but child Mike—the boy whose memories were so painful my mind had sealed them away.

Looking at Westen was like staring at my uncorrupted self before life's hardships—before whatever traumas had caused my mind to erase entire years of my childhood. The heaviness in my chest wasn't about him; it was the weight of my own buried past rising to the surface, demanding to be felt.

Each time I looked into his innocent eyes, the wounded parts I'd spent decades running from stood before me, impossible to ignore. My son had become the doorway to my deepest healing. The relief of not being a heartless father was replaced with the burden of facing unresolved feelings locked away my entire life.

This wasn't genetic inheritance. This was emotional excavation—my son unearthing what I had buried, reflecting back the very parts of myself I most needed to reclaim.

The Justice Seeker

With Brycen, the mirror revealed a dimension of myself I had long wrestled with but never fully understood. I watched him relentlessly pursuing fairness in every situation—meticulously dividing a bag of chips among his brothers, his mind calculating perfect equality with the precision of a courtroom judge.

"That's not fair! Why does Keaton get that when two weeks ago, he had one and I didn't?" he would challenge.

"Because that was for his birthday," I'd explain, exhausted.

"What about when Gryffin got 3 last Tuesday and Westen had 4 last Friday?" he'd counter, his memory for inequities flawless, his arguments maddeningly valid. Each point he raised was technically correct—a logical fortress I couldn't easily dismantle, all deployed over something as trivial as a lollipop.

One afternoon, worn down by his endless accounting of who-got-what-when, I snapped: "Why do you always think everything has to be fair? In the real world, nothing is fair. It's just what it is."

The harshness in my voice shocked us both. His eyes widened, not from fear but from genuine confusion. How could anyone not care about fairness? The concept seemed to violate something fundamental in his understanding of how the world should work.

Years later, my DNA results revealed something remarkable: I carried an extraordinarily rare "fairness gene"—a genetic predisposition toward equity that fewer than 5% of people possess. In that moment of scientific revelation, Brycen's behavior transformed from merely annoying to profoundly illuminating.

I suddenly understood why his fairness obsession triggered such disproportionate frustration in me. My harsh criticism wasn't about his behavior at all—it was about my own painful reconciliation with a world that had repeatedly violated my innate sense of justice. Every time he insisted on perfect fairness, he was reminding me of a core value I had partly abandoned after years of disappointment.

Through Brycen's unflinching commitment to equity, I was confronting not just a personality quirk in my son, but my own genetic inheritance and the emotional wounds it had created as I learned that the world rarely meets this innate expectation for fairness. In his stubborn insistence on justice, I saw the reflection of my younger self—before I'd learned to accommodate an imperfect world.

The Pattern Recognizer

Then came Gryffin, whose mind moved in mental matrices I recognized intimately. Sitting together predicting the Sonic movie plot, finishing each other's thoughts about what would happen next, was like watching my own cognitive architecture externalized. In his rapid-fire pattern recognition, I saw both the gift and burden of how my own mind works.

At 7 years old, we were watching Sonic The Hedgehog:3 movie together and he says "I didn't even see this before" but then continued to accurately predict the plot of the movie. I excitingly paused it and dug deep wondering if this is confirmation that he too sees the patterns I used to think everyone saw. The rest of the movie we took turns guessing what happens next. In his eyes, I saw the reflection of my own perpetual processing—the blessing and curse of seeing connections that others miss.

But the mirror extended beyond his analytical abilities. When monitoring his screen time, I noticed another pattern that instantly struck me: Gryffin would download apps by the hundreds. While his brothers had 30 apps max, Gryffin's tablet was a graveyard of digital exploration—constantly downloading new applications until running out of memory, then deleting and repeating the cycle all over again.

What truly revealed the reflection was discovering that despite his collection of hundreds of apps, he only used two consistently. The rest were part of a restless cycle—downloaded in a burst of curiosity, barely explored, then abandoned for the excitement of the next discovery.

In that moment, my own reflection hit me with startling clarity. I saw the exact pattern that defined my adult life—the endless shelf of unfinished passion projects, the equipment purchased for hobbies barely started, the courses enrolled in but never completed. Even though Gryffin's cycle played out through child games, it mirrored my exact habit: being captivated by a new idea only to be distracted by the excitement of another. We shared the same restless curiosity, the same thrill of novelty, and the same inability to focus and choose just one path.

Through Gryffin, I wasn't just seeing a child with too many apps—I was witnessing the earliest manifestation of a cognitive pattern that would shape his entire relationship with the world. More profoundly, I was seeing my own mental landscape reflected back at me with uncomfortable precision. His digital restlessness wasn't childish distraction; it was the first emergence of the same pattern-hungry, novelty-seeking mind that defined my own journey through life—with all its creative advantages and frustrating limitations.

The Science Behind the Mirror

What I was experiencing with my sons isn't just poetic metaphor—it's rooted in neuroscience. The discovery of mirror neurons in the early 1990s revealed something remarkable about the human brain: it contains specialized cells that fire both when we perform an action and when we observe someone else performing that same action. This neural mirroring system doesn't just apply to physical movements—it extends to emotions, intentions, and even pain responses.

Children's developing brains are particularly attuned to this mirroring process. Their mirror neuron systems are exquisitely sensitive, designed to absorb not just the explicit lessons we teach them but the implicit patterns of how we navigate the world. This is why a parent who preaches honesty but practices deception will inevitably raise a child who notices the contradiction, regardless of the words spoken.

Research by developmental neuroscientists like Allan Schore has shown that parent-child dyads actually co-regulate each other's nervous systems. A parent's stress response triggers corresponding neural activity in their child's brain. When a parent becomes anxious, their child's brain doesn't just notice it—it begins to mirror that same pattern of activation.

This biological synchrony explains why the patterns we haven't processed within ourselves inevitably emerge in our children, sometimes in ways that mystify us until we recognize the reflection. The very neural architecture of human development ensures that children become living mirrors of our resolved and unresolved emotional material.

Even more fascinating is how intergenerational trauma manifests through this mirroring mechanism. Psychiatrist and trauma researcher Bessel van der Kolk explains that "the body keeps the score"—meaning that trauma responses get encoded in our physiology, even when we've mentally blocked the triggering events. Like my missing third-grade year, these experiences don't simply disappear; they get stored in implicit memory systems that influence our behaviors and responses without our conscious awareness.

When children sense these implicit patterns, they don't just observe them—they incorporate them. Studies of Holocaust survivors and their descendants have shown how trauma responses can be transmitted across generations, not just through storytelling or parenting practices, but through biological mechanisms that we're only beginning to understand.

This isn't just psychological theory—it's observable in the attachment patterns that form between parents and children. The Adult Attachment Interview, developed by Mary Main and her colleagues, demonstrates that the way parents make sense of their own childhood experiences strongly predicts how their children will attach to them. Parents who haven't reconciled their difficult early experiences tend to have children who develop the same attachment patterns, perpetuating the cycle.

But here's the hopeful part: this same research shows that what matters most isn't whether parents had difficult childhoods, but whether they've made sense of those experiences. Parents who have reflected on and processed their early challenges—who have developed what researchers call "earned secure attachment"—can break the cycle, raising securely attached children despite their own difficult beginnings.

This is why our children's mirroring is such a gift, even when it's painful. It offers us a chance to see and heal the parts of ourselves we might otherwise never access.

The DNA Connection: Reshuffled Inheritance

My four sons represent four distinct personalities, four unique ways of seeing the world—yet every piece of them came from the same raw genetic material. My DNA, reshuffled and recombined, distributed across four boys who each express it in their own way.

My genes are a deck of cards, shuffled and dealt out differently to each of them. Some got my hyper-speed thinking, others inherited my impulsivity or my deep emotional processing, while some may have received traits I never fully developed—like the athletic potential my genetics hinted at but I never explored.

There's no roadmap to this inheritance. It's not a clean split where each kid gets exactly 50% of me and 50% of their mother. Instead, my boys each got a randomized remix of our traits.

Maybe one of them has my risk-taking but none of my social adaptability—meaning they'll charge headfirst into ideas but struggle to convince people to follow. Maybe another has my intelligence and emotional depth—but none of my drive for novelty, making them more structured but less restless. Maybe one got the athletic endurance I never used, while another inherited my need for mental stimulation but none of my tolerance for discomfort.

As a new, naive father, my initial instinct was to be fair by treating all my children identically. I quickly realized how wrong that approach was. I learned to be tougher with Brycen because that's who he is—treating him with less firmness than what he's built to handle would be a disservice. Keaton, while not weak, is simply wired differently and needs communication wrapped in extra care. Brycen needs the same love but at different times and in different proportions. I need to be mindful not to make Westen feel invisible, while knowing Gryffin wouldn't take offense.

It's impossible to treat all your kids the same and still have them feel happy, protected, fulfilled, and understood. Having four unique combinations of DNA blueprints creating these vastly different little boys provided an extraordinary testing framework without even trying.

The discovery of my own hybrid genetic profile was illuminating not just for understanding myself, but for recognizing how these traits had been reshuffled and distributed across my four sons. I began to see how Gryffin inherited my pattern recognition, how Keaton got my emotional sensitivity, how Brycen received my challenge-seeking nature, and how Westen embodied my capacity for deep connection.

But the most profound realization wasn't about which genetic traits each son inherited—it was how those traits interacted with their environments and experiences, including their interactions with me. When Gryffin and I sat watching that Sonic movie, taking turns predicting the plot twists before they happened, we weren't just sharing a genetic ability to see patterns—we were reinforcing and developing that ability through our interaction.

This is where the mirror effect transcends simple genetic inheritance. Our children don't just passively receive our genetic traits; they actively engage with us in ways that reflect those traits back to us, often revealing aspects of ourselves we haven't fully acknowledged.

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Value

Like many parents, I had no real roadmap for "how to parent." I generally stuck to familiar methods, rarely deviating from what seemed conventional. Looking back, I can humbly admit that a constant, low-grade anxiety about my parenting choices was always present, though I doubt I would have acknowledged it at the time.

Then something happened that genuinely changed everything.

We had just moved into a new house. Their mother dropped the boys off at 3 PM, but I still had work to finish. Understanding their expectations for attention, I realized that ignoring them for two hours would make them restless, likely leading to behavior that would eventually frustrate me. So I tried something different.

Rather than assigning tasks, I appointed each child with a title and role. Brycen became "the Cook," responsible for preparing all meals. Keaton was named "Laundry Master," tasked with washing, drying, and folding clothes. Westen was designated "Garbage Commander," in charge of taking out trash and sweeping floors. Gryffin became the "Dishwashing Wizard." It was a spontaneous experiment—I had no idea what would happen.

After explaining each responsibility and providing basic instructions, I returned to my computer to finish working. Two hours later, when I emerged and found the house quiet, my first reaction was panic. But what I discovered astonished me.

All the dishes were washed and sitting in the drying rack. The garbage had been taken to the street, and the floors were swept clean. Lunch had been prepared and served to everyone. Two loads of laundry were washed, dried, and put away—even the lint trap had been cleaned after each cycle.

What struck me even more than the completed tasks was their demeanor: they were all beaming with excitement and pride. This contrast to the usual resistance that comes with assigned chores confused me until I recognized what was happening: they were experiencing intrinsic value.

Children fundamentally want to feel valued. They need to feel purposeful—that they're contributing meaningfully to something larger than themselves. When this happens, their confidence soars and their attitudes transform immediately. As a parent, witnessing this shift is profoundly rewarding.

When Trust Meets Control: The Grandparents' House Experience

After discovering this approach with my children, I believed I'd found a secret that could transform family dynamics everywhere. I was particularly excited to demonstrate this revelation during our next visit to my parents' house. Here was an opportunity to simultaneously help my parents with their household tasks while reinforcing my children's newfound sense of purpose and capability.

The anticipation among my children was palpable. Brycen kept expressing how excited he was to cook eggs for his grandmother, imagining how much she would enjoy them. Westen eagerly planned to organize the basement that was cluttered with unused toys. When my parents left for a doctor's appointment the next morning, we saw our chance to create what I imagined would be a wonderful surprise.

The children immediately sprang into action with enthusiasm. Keaton tackled the backlog of laundry, working through one of four accumulated loads. Westen managed all the garbage collection, cleaned the litter boxes, and swept and mopped the floors. Brycen cleaned and organized their refrigerator while beginning to prepare lunch for their return. All of us waited gleefully, imagining their faces when they discovered how much had been accomplished in their absence.

The reaction we received, however, was nothing like what we had anticipated. Instead of appreciation, my parents appeared visibly upset. My father, unable to contain his discomfort, demanded to know who had dared to touch the washing machine. My mother, who grew up in an era when appliances were expensive investments that lasted decades, had developed specific routines around their use—routines that provided stability and predictability in their home. They anxiously questioned where the garbage had been taken and why we had reorganized their belongings without prior approval.

The most heartbreaking moment came when Brycen's excited expression turned to disappointment as they took the spatula from his hand, saying, "Don't worry, I'll do it." The entire scene revealed a complex generational disconnect—what we saw as helpful initiative, they experienced as an unexpected disruption to established patterns that had served them well for years.

I recognized that my parents weren't simply unwilling to trust. Their response reflected a different generational approach to household management and childhood roles, combined with the natural desire for consistency that often becomes more pronounced with age. For them, maintaining familiar systems wasn't just about control—it represented security, reliability, and the comfort of knowing exactly where everything belonged in the home they had carefully maintained for decades.

The impact on my children was immediately visible. Although they attempted to shrug off the rejection, I could see their sense of self-worth visibly diminish. The confidence and pride that had been so evident just hours before seemed to collapse, leaving them as mere shadows of their former enthusiastic selves.

This experience revealed another layer of the mirror effect—how unexamined patterns and generational differences can unintentionally undermine others' sense of purpose and capability. My parents weren't intentionally dismissing my children's efforts; they were responding from their own life experiences and values around home management and appropriate roles for young children.

The incident offered a powerful contrast that further solidified my understanding: different generations often have fundamentally different approaches to trust, autonomy, and responsibility. What appears to one generation as helpful initiative may feel to another like unwelcome interference. The difference lies not in the universal need to feel valued, but in deeply ingrained beliefs about how that value should be expressed and recognized across different age groups and contexts.

This contrast between my children's experience at our home versus at their grandparents' house illustrated perfectly how the same fundamental human need—to feel valued and trusted—exists across generations. The difference lies not in the need itself, but in whether that need is recognized and honored or inadvertently suppressed by our own unresolved patterns.

That's when I saw the mirror effect again. This desire isn't unique to children—it's universal. All humans want to feel valued and purposeful. The insight seemed so obvious that I was surprised it hadn't registered as common sense before.

The distinction, while subtle, creates enormous differences in outcomes: No one—child or adult—wants to be told what to do. However, when you embed trust and privilege into a role where someone has autonomy while still receiving guidance, everything changes.

This realization contradicts how many view childhood responsibilities. When people see my four boys proudly helping me move items at the storage unit, the most common comment is something like, "child labor sweatshop." What these observers miss is that by trusting children with responsibilities, the intrinsic value of feeling useful far outweighs the typical extrinsic rewards they might get from Fortnite or Roblox.

I've since applied this understanding to my own life and confirmed its universality. We all share the fundamental desire to be seen, to feel useful, and to have genuine purpose. Nobody—regardless of age—wants to simply be told what to do.

This insight represents a sacred paradox of parenthood: while we believe we're raising our children, they're actually helping complete our own development. They excavate aspects of ourselves we've never fully integrated, understood, or healed. They become our greatest teachers—if we have the wisdom and courage to recognize these lessons.

Our children arrive not just as empty vessels for us to fill with knowledge, but as mirrors precisely crafted to reflect back our unfinished growth. They don't just carry our genetic future—they carry the possibility of healing our emotional past. In them, we find our fragmented selves, waiting to be recognized, accepted, and finally made whole.

The children we think we're raising are actually raising us. And in this perfect symmetry lies perhaps life's most profound opportunity for transformation.

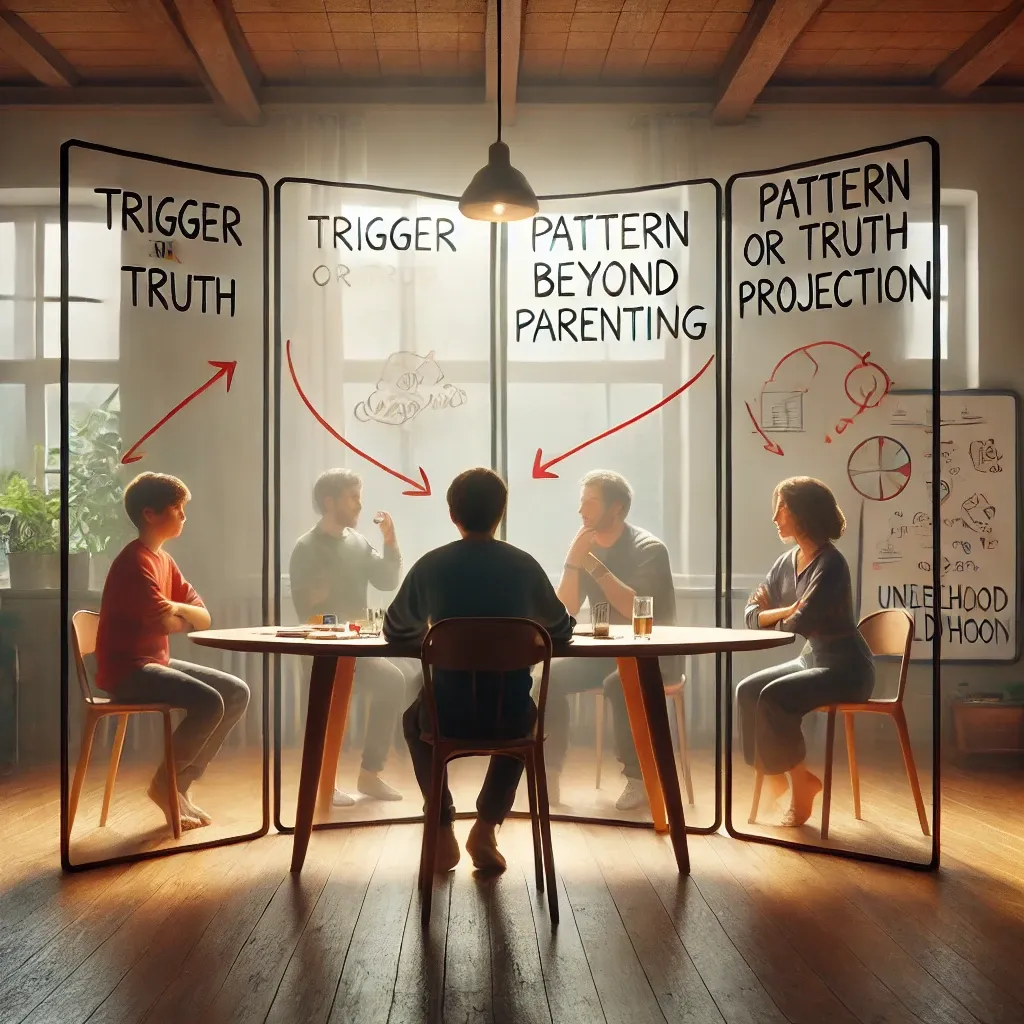

Developing Your Parenting Shadow Map

So how do we use this mirror effect productively rather than just being triggered by it? How do we transform these reflections into opportunities for growth rather than sources of frustration?

Creating Your Parenting Shadow Map

The first step is developing what I call a "parenting shadow map"—a framework for identifying your own unresolved patterns as they emerge in your interactions with your children. Here's how to begin creating yours:

- Notice disproportionate reactions. When your emotional response to your child's behavior seems bigger than the situation warrants, you've likely hit a shadow spot—a place where your child is triggering an unresolved issue from your own past. For me, Brycen's obsession with fairness triggered an outsized frustration that revealed my own painful reconciliation with a world that had repeatedly violated my innate sense of justice.

- Ask the reflection question. When triggered, pause and ask yourself: "What does this remind me of from my own childhood?" Be brutally honest. Often the answers will surprise you, revealing connections between your current reactions and past experiences you haven't fully processed.

- Distinguish between your issues and your child's development. Not every challenging behavior is a mirror. Children go through normal developmental stages that can be difficult without necessarily reflecting your unresolved patterns. The key is noticing the emotional intensity of your reaction—normal developmental challenges might frustrate you, but they don't typically trigger deep emotional distress.

- Look for patterns across relationships. If you find yourself having similar reactions to different children or even to other adults in your life, you're likely encountering a core unresolved pattern. These consistent triggers across relationships often point to your most significant growth opportunities.

- Notice where you feel most challenged as a parent. The aspects of parenting that feel most difficult often reveal where you had insufficient modeling or support in your own childhood. If maintaining boundaries consistently feels impossible, you might be struggling with boundary issues from your own upbringing.

Here's a concrete example from my experience: When I noticed Gryffin's habit of downloading hundreds of apps but only consistently using two, I felt an uncomfortable recognition that went beyond mere observation. His digital restlessness—constantly seeking new apps only to abandon them for the next discovery—mirrored my own adult pattern of accumulated passion projects and hobbies started but never completed. My reaction wasn't about his behavior; it was about confronting my own restless mind and its challenges with focus and completion.

Another powerful example emerged with Westen. The inexplicable heaviness I felt around him—even questioning if I loved him as much as his brothers—wasn't about him at all. It was about how he reflected "child Mike," that uncorrupted version of myself before life's hardships. The discomfort I experienced was my buried childhood self rising to the surface, demanding acknowledgment after decades of avoidance.

The shadow map isn't about self-blame—it's about self-awareness. It's not that we're intentionally passing down negative patterns; it's that we can't help transferring what we haven't transformed. The good news is that awareness itself begins the transformation process.

Breaking Generational Patterns

Once you've identified these mirror patterns, you can begin the work of interrupting negative cycles. Here are strategies that have worked for me and for many parents I've shared these concepts with:

- Name it to tame it. Simply labeling your emotional reaction in the moment can create enough distance to interrupt the automatic response. When I feel that flash of frustration at Brycen's relentless pursuit of fairness, I internally name it: "This is my own fairness trigger reflecting my genetic predisposition and personal history, not just about his behavior."

- Create a pause practice. Develop a consistent way to pause when triggered before responding. It might be taking three deep breaths, silently counting to ten, or physically stepping back. This creates space between trigger and response where new choices become possible.

- Develop a trigger phrase. Create a simple phrase that reminds you what's really happening when you're triggered. Mine is "This is about me, not him." These few words help me remember that my intense reaction likely has roots in my own history.

- Share your journey. Age-appropriately, let your children know when you're working on your own patterns. This doesn't mean burdening them with your emotional processing, but simply acknowledging, "I'm working on my big reactions when I feel challenged."

- Repair ruptures. When you inevitably get triggered and react in ways you later regret, make it right through sincere apology and changed behavior. This not only heals the relationship but models for your children how to take responsibility for their own reactions.

- Seek support. Breaking generational patterns often requires outside perspective from a therapist, coach, or supportive community. We can't see our blindspots without mirrors—both the mirrors our children provide and the mirrors of compassionate outside observers.

The power of breaking these cycles extends far beyond your relationship with your children. When you heal these patterns, you're not just becoming a better parent—you're literally changing your family's future. This is generational healing in action.

I've seen this in my own parenting journey. By recognizing how my inexplicable heaviness around Westen reflected my own unresolved childhood self, I've been able to process that discomfort rather than projecting it onto him. This doesn't just improve our relationship—it helps heal the wounded parts of my own inner child that I had spent decades avoiding.

Similarly, by understanding Gryffin's app-downloading pattern as a mirror of my own challenge with focus and completion, I can guide him with compassion rather than criticism. Instead of seeing his digital restlessness as merely a bad habit to correct, I recognize it as the early manifestation of a cognitive pattern we share—one with creative advantages that can be channeled productively with the right support.

With Brycen, understanding that his obsession with fairness mirrors my own genetic predisposition has transformed our interactions. Rather than reacting with frustrated dismissal when he meticulously divides everything equally, I can now appreciate this quality as a core value we share. I can help him navigate a world that doesn't always honor this sense of justice, while preserving the integrity of his natural inclination toward equity.

In each case, recognizing the mirror effect has allowed me to separate my own unresolved issues from my children's natural development. This awareness creates space for them to grow into who they truly are, rather than being constrained by my unconscious reactions to what they reflect back to me.

The Mirror Effect Beyond Parenting

While I've focused on how this mirror effect operates in parent-child relationships, the same principle applies to all significant relationships in our lives. Romantic partners, close friends, even challenging work relationships often trigger our unresolved patterns and offer similar opportunities for growth and healing.

The colleague who consistently pushes your buttons may be reflecting aspects of yourself you haven't fully acknowledged. The recurring conflicts in your romantic relationship might reveal patterns you developed long before you met your partner. Even pet peeves and everyday irritations can be windows into unprocessed material.

The mirror effect operates anywhere there's sufficient emotional investment for our unconscious patterns to emerge. The closer the relationship, the more powerful the mirroring potential.

What makes parent-child relationships especially potent mirrors is the combination of genetic connection, intense emotional bonding, and the power differential that exists. Our children reflect not just what we consciously show them but what we unconsciously carry—and they do so with a biological precision and emotional intensity that can't be ignored.

Yet the principles for working with these reflections remain the same regardless of the relationship: notice disproportionate reactions, question what they might be reflecting from your past, distinguish between your issues and the other person's behavior, look for patterns across relationships, and develop practices that help you respond consciously rather than react automatically.

In my professional relationships, I've found that people who trigger strong negative reactions in me often possess qualities I've disowned in myself. The colleague whose self-promotion irritates me might be reflecting my own discomfort with visibility and recognition. The team member whose disorganization frustrates me might be triggering my fear of the chaos I work so hard to keep contained.

Recognizing these mirrors doesn't mean excusing problematic behavior in others. It means understanding the difference between a reasonable response to someone else's actions and a triggered reaction that reveals your own unresolved patterns. Both can exist simultaneously, but healing happens when you address the latter even as you set appropriate boundaries around the former.

Returning to the Memory Gap

This brings me back to that 7-Eleven encounter—that moment when I discovered a year of my life had been erased from my conscious memory. What I've come to understand through parenting my boys is that the pieces of ourselves we can't remember—or won't acknowledge—don't simply disappear. They continue to influence how we move through the world, how we parent, how we love, how we work.

And most powerfully, they emerge in our relationships with our children, who become living reminders of what we've forgotten or disowned. They become the custodians of our missing pieces, reflecting back to us what we cannot see directly in ourselves.

Sometimes those reflections are painful. Sometimes they trigger shame, anger, grief, or confusion. But they always offer an opportunity for healing—for reclaiming the parts of ourselves we've lost or never fully developed.

This is the ultimate gift of the mirror effect: our children don't just inherit our unresolved patterns—they offer us a chance to resolve them. They don't just reflect our wounds—they reveal pathways to healing them. They don't just show us who we've been—they show us who we might become if we're brave enough to face the reflections they provide.

And perhaps most illuminating of all is how our children ultimately become our greatest teachers. While we're busy trying to figure them out—observing their traits, wondering which parts came from us—they're busy reflecting back to us sides of ourselves we never fully understood. In watching my sons develop, I've discovered more about my own nature than I ever could have learned alone. Their struggles illuminate my own. Their strengths reveal possibilities within myself I hadn't recognized.

This is the ultimate mirror effect of parenting: our children show us who we are, even as we think we're showing them who they might become. And sometimes, the most profound discoveries about ourselves come through the eyes of those we're trying so hard to understand.

Try This: Creating Your Mirror Map

- Notice triggers. For one week, pay close attention to moments when your child's behavior triggers an emotional reaction that feels disproportionate to the situation. Write down:

- What your child did or said

- How you felt emotionally (anger, shame, anxiety, etc.)

- How intensely you felt it (1-10 scale)

- Your first impulse for how to respond

- Find the reflection. For each trigger, ask yourself:

- "What does this remind me of from my own childhood?"

- "When have I felt this same emotion in my past?"

- "What message did I receive about this behavior or feeling growing up?"

- "What unmet need might this be touching in me?"

- Connect past and present. Journal about how your past experiences might be shaping your current reactions. Look for patterns across different triggering situations.

- Create your reminder phrase. Develop a short, powerful phrase to use in the moment when triggered that reminds you what's really happening. Examples:

- "This is my history, not their behavior."

- "This belongs to little me, not to them."

- "This is about my past, not their future."

- Practice a new response. Choose one triggering scenario and plan a different way to respond when it happens again. Practice this response mentally, imagining yourself choosing this new path even when emotionally triggered.

The goal isn't to never get triggered—that's not realistic. The goal is to recognize the trigger as information about your own unresolved patterns, creating space to respond consciously rather than react automatically. Each time you do this, you're not just changing your relationship with your child—you're healing your relationship with yourself.